To achieve robust, “effective” (as in SOX 404) internal controls and related best practices in light of COSO (2013), SOX, and US GAAP/IFRS, etc., I would employ the top-down, risk-based (audit) approach, as guided by SEC/PCAOB per Audit Standard No. 5 (AS 5) not only at an entity level but also at a process level.

Otherwise, external auditors would never be satisfied and keep finding control deficiencies (even if they issued their clean, unqualified opinion on company’s controls under SOX 404). They would do so unless management eliminated potential audit adjustments, or frankly, errors/misstatements.

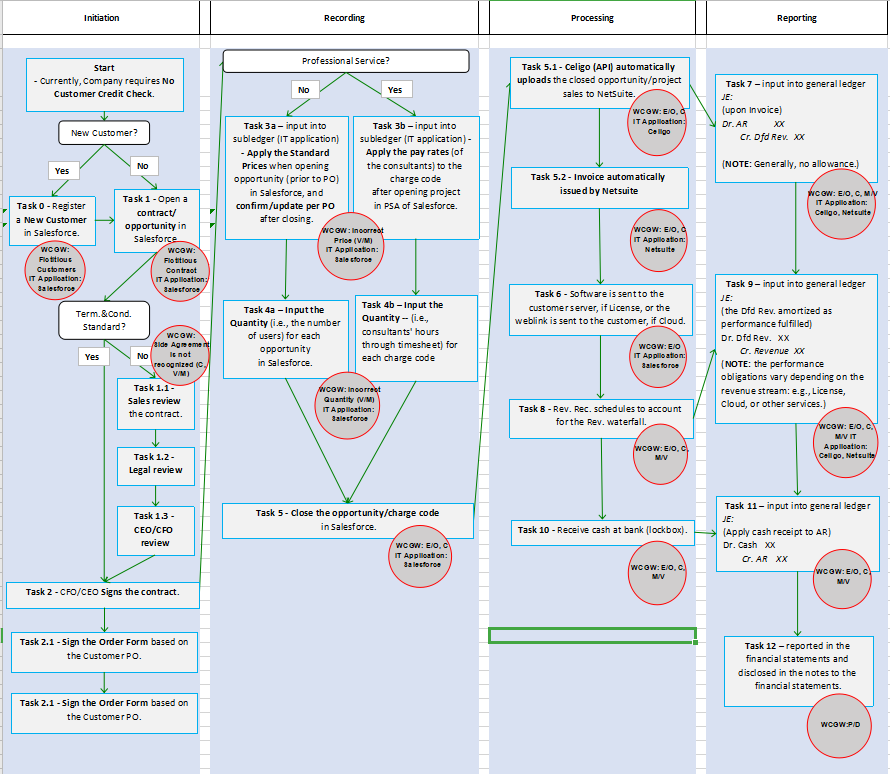

To avoid such an error or misstatement, the company has to design preventive controls (as opposed to detective controls) at every critical data-path, or Likely Source of Potential Misstatement (LSPM as in AS 5) within each transaction cycle: i.e., (Vendor Management/)Procure to (Inventory/Fixed Assets/Payroll to Accounts Payable to) Pay (P2P), (Customer Credit Management/)Order to (Accounts Receivable to) Cash (O2C), and Record/Closing to Report (R2R).

Detective controls are, in nature, to detect errors/misstatements (which have already recorded in ERP through a critical data-path) to correct. Unless related preventive controls (which oftentimes can be automated) are in place to prevent any errors/misstatements, the errors are to recur (to be detected and corrected) every year.

To satisfy the auditor and ultimately the Audit Committee (AC)/Board of the Directors (BoD), the management needs to put preventive controls at each critical data-path so that it can eliminate the possibility of, or prevent, any potential (material) misstatements.

To mitigate their Audit Risk, the auditor would never take the control reliance approach unless management has adequately mitigated (or controlled) misstatement risks or prevented potential, material misstatements.

The trick is that neither the auditor nor the BoD, or the “oversight” body (as in COSO), would specifically advise/instruct the company management on how to design and operate preventive controls.

Design Preventive Controls in line with the Top-Down, Risk-Based (Audit) Approach

By employing the top-down, risk-based approach, at a process level (i.e., at the P2P/O2C/R2R transaction level), I would ultimately design preventive controls (to rectify/mitigate the root-cause of a potential misstatement) at every LSPM, so that the company can provide the auditor with good reasons to believe that management’s controls are in fact so “effective” (as in SOX 404) as to take the control reliance approach.

(Note that, complying with COSO Principles at an entity level, control authorities must be delegated to management by the oversight body, through authorized Policies and Procedures (and Roles and Responsibilities), and further to junior manager levels, who in turn are accountable for the effective controls to be adequately put in place. See this post for more details on this.)

At a process level, misstatement risks should be defined at each LSPM (hence the “risk-based”) first at the financial statement caption level (i.e., the top), and then the risks should be broken down to the general ledger (G/L) level, further to the sub-ledger level, and finally to the transaction initiation level (hence the “top-down”).)

(Refer to para. 21 of AS 5 about the top-down approach from auditors’ perspectives.)

The key here is for the company to identify all the critical data-paths (i.e., LSPM), not more or less than necessary, in each of the process cycles.

(For more common mistakes observed in practice of identifying LSPM’s, refer to my blog posts here and here.)

This is literally “critical” because redundant (or not critical) data-paths, if identified, would confuse and allow the company management to come up with redundant misstatement risks; thereby misleading them to design redundant internal controls (to attempt to mitigate the redundant risks).

For example, “setting up budgets” is not an LSPM because it will not affect the financial statements; i.e., regardless how much actual results divert from the budget, management must report the actual results.

For more common mistakes observed in practice concerning controls, refer to my blog post.

Next, take another LSPM example, which is not necessary redundant but pertains to a detective control, such as;

LSPM 0: “In preparing the AR Aging report, Accountant could overlook a customer account, whose AR outstanding balance has exceeded it’s credit limit authorized by the BoD, and fail to post a bad debt expense for the overage.”

Key Risk 0: an overstatement of (Dr.) AR (Cr.) Sales with assertions being Existence/Occurrence (or,

an understatement of (Dr.) Bad Debts (Cr.) Allowance For Doubtful Accounts with assertion being Completeness).

The hypothetical control to mitigate the Key Risk 0, as an example, may be such that;

Control 0: Detective, IT Dependent Manual –

“Accounting Manager reviews and approves the bad-debts/AFDA entries as of a balance sheet date.”

The Control Attributes (or Control Objectives) should be;

Attribute 1 – The Manager’s bad-debts/AFDA approval is authorized by the BoD in the Policies and Procedures and the Manager’s review competence is authorized (by the BoD) in the Roles and Responsibilities.

Attribute 2 – In his/her review (for the approval), the Manager validates the accuracy of the supporting data set: e.g., the credit limits/AR Aging, processed by the system/ERP as authorized, properly in the correct period.

In order to improve the Control 0 and replace it with a preventive, automated control, I would ask myself as to what misstatement risk needs to be mitigated.

The risk is clearly Key Risk 0 above.

Then, I would move on to clarify as to what the critical data-path (LSPM) will be when I want to automate to “prevent” the data error in the period-end bad-debts/AFDA entries.

The critical data-path would be the data-processing on the periodic bad-debts/AFDA entries at the balance sheet date, and the hypothetical LSPM 1 could be such that;

LSPM 1 “Upon fulfilling required “performance obligations (as in ASC 606)” (and issuing an invoice, which is configured to automatically post an AR/Sales entry, for the amounts of the agreed-upon price times incurred hours (in case of a service agreement) in the ERP), Revenue Accountant could input (in the ERP) the sales amounts (for a customer), which would marginally exceed the credit limit as a result of the reciprocal AR outstanding surpassing the limit.” (The corresponding misstatement risk is the same as the Key Risk 0.)

The LSPM1 specifically pertains to the “collectibility” element in the “identify the contract” step under ASC 606.

Accordingly, an example of key automated control at the LSPM 1 should be such that;

Control 1: Preventive, Automated “The sales ledger automatically;

- refers to the customer database and verifies the invoice amounts not causing the AR outstanding (including the invoice) to exceed the customer’s (authorized) credit limit, and

- if exceeded, the system/ERP posts a bad-debt/AFDA entry for the amount of the overage.”

Attribute 1 – ITGC (IT General Controls) is tested and concluded to be effective.

Attribute 2 – The automated bad-debts/AFDA approval (and the posting) is authorized in Policies and Procedures.

Attribute 3 – The system is properly configured to refer to the correct customer in the customer database.

Attribute 4 – In case of the overage, the system is properly configured to post the correct amounts and accounts.

As a result, I would make the (preventive, automated) Control 1 be the Key Control (for the Key Risk 0) and the (detective, (IT-dependent) manual) Control 0 be a Compensating Control (if necessary).

(Note that, in this example, the Control 1 focuses on the collectibility element and that there are other factors (e.g., pricing, quantity/hours definitions, the descriptions of performance obligations, etc.) in the “identify the contract” step to satisfy the ASC 606 revenue recognition requirements.)

As illustrated above, we should be able to design “effective,” preventive controls (to control “how to process” the data) by identifying the root-cause of a potential misstatement, or an LSPM, at every critical data-path within each cycle as opposed to detective controls (to directly/substantively “control” data), which simply correct misstatements.