A typical pitfall you might fall into, when designing financial controls, is to take what I call the “Bottom-Up, Control-Based” approach (as opposed to the Top-Down, Risk-Based” approach as guided in Auditing Standard No. 5 (AS 5) issued by SEC/PCAOB).

That is, without the proper yard stick (i.e., the Top-Down, Risk-Based approach) that guides you through in identifying key financial risks (i.e., critical data-paths, LSPM (Likely Source of Potential Misstatement as defined in AS 5), or WCGW (What Could Go Wrong)), you would end up with either missing key risks and/or corresponding controls (in which case the controls would be ineffective) or identifying them redundantly (then the controls would be inefficient).

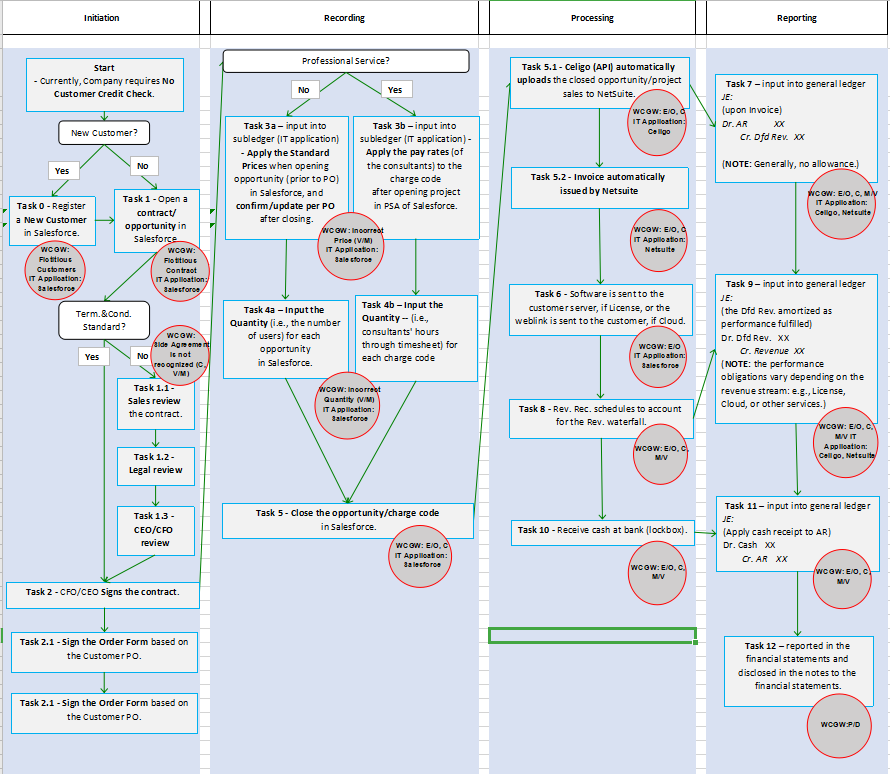

By applying the Top-Down, Risk-Based approach, when defining key financial (or misstatement) risks at a process level or at each LSPM in an end-to-end transaction cycle (e.g., Order to Cash, Procure to Pay), you would be able to identify all critical data-paths, or LSPM, (not less or not more than necessary) within each process cycle; thereby ensuring that you define all the key financial risks, with proper financial statement assertions, and design effective internal controls.

Practically Applying the Top-Down, Risk-Based Approach at a Process Level

For example, in order to identify the LSPM’s, you would start from the Reporting phase, where the LSPM would be related journal entries getting posted to the G/L (general ledger), and move on backwards to identify another LSPM where the underlying journal entries are Recorded to the sub-ledger. Then, you would further move on to the Processing and Initiating the underlying data before the Recording phase.

The approach would be “Top-Down” because you would start from the Top, or the G/L, and proceeding back, or Down, towards the Processing/Initiation phases when identifying the critical data-paths (LSPM’s) within a process cycle.

Now that you have identified all the critical data-paths/LSPM’s (and not more or not less than necessary/complete), you should be able to define key financial/misstatement risks with proper financial statement assertion (i.e., Existence, Completeness, Valuation).

The approach would be “Risk-Based” because you would define the key financial Risks first so that you can Base on those when designing key controls to adequately mitigate the Risks.

Note that you are NOT supposed to start designing the key financial controls that you think you should have (which would be what I call the “Control-Based” approach) because, if you did, you would never know what (and how many) financial risks (and underlying LSPM’s) are necessary and complete to begin with.

Note also that you would NOT start identifying the critical data-paths from the (data) Initiation phase (which I call the “Bottom-Up” approach) because you would want to avoid the situation where you mistakenly identify a data-path to be critical when it’s actually not; i.e., it’s not critical if the data-path you have identified does NOT flow into or affect the financial statements .

Examples of Common Mistakes (in Identifying “Risks”)

For example, “A budget is inaccurately measured/valued” is NOT a financial/misstatement risk as it will NOT affect the financial statements in any way; therefore, even if the budget is initiated and recorded in a computer application somehow, it cannot be a critical data-path.

Another example that could be caused by taking the inappropriate “Control-Based” approach; “Sales manager does not review/approve a customer sales order.” is NOT a financial/misstatement risk (or an inherent risk as in the CRA, Combined Risk Assessment, considered by external auditor) but a control risk (as in the CRA), which means that the “sales manager’s review” is a control and NOT a critical data-path (or a LSPM).

(In other words, the description is simply stating the fact that the particular “sales manager’s review” control does not exist.)

The proper description of the particular LSPM would be something like, “A fictitious customer sales order is inputted in Salesforce by sales personnel (Assertion: Occurrence/Existence.),” and/or “Sales order inputted in Salesforce is incomplete (Assertion: Completeness),” etc.

Those are the reasons why and how the Top-Down, Risk-Based approach needs to be appropriately applied at a process level (in compliance with the AS 5 as guided by SEC/PCAOB).

Work Sample of the Order-to-Cash Flowchart

This flow-chart is presented with the LSPM being referred to as WCGW, or What Could Go Wrong (and w/ the Assertions being referenced as E/O (Existence/Occurrence), C (Completeness), etc.).

Another Common Pitfall

Speaking of the “pitfalls,” another one that is commonly found would be related to the Reporting (or Record-to-Reporting/R2R, depending on the preference of how to call it) cycle.

Nowadays, the Revenue (i.e., Order-to-Cash) and AP (i.e., Procure-to-Pay) cycles, particularly the part of the Recording and Reporting phases, are automated (e.g., typically the records on the sub-ledgers are automatically posted to the G/L); therefore, when it comes to the Reporting cycle, the most important LSPM would be typically a manual journal entry, whether it’s AR reserves, contra-sales entries, investment valuation adjustments, pension liabilities, taxes, stock compensation, etc. etc.

The pitfall I am talking about here is the fact that management tend to consider “WHETHER or not the numbers (i.e., the manual entries) are accurate” a control testing while, in fact, the proper control testing of any of the manual entries would be “HOW effectively the management mitigates the risk of related misstatement, or LSPM.”

Here, to test “WHETHER or not the manual entries are accurate” is a substantive testing (as auditors would perform) and not the control testing.

Auditors test the manual entries (i.e., numbers) “substantively” to assess their Audit Risk (as in their Combined Risk Assessment, or CRA) whereas, if they want to assess Control Risk (as in the CRA), they would test “whether or not the related internal controls are effective (under SOX 404),” or “HOW effectively the management mitigates the risk of related misstatement (at LSPM)”.